渡辺利夫「神経症の時代ーわが内なる森田正馬 (The Age of Neurosis)

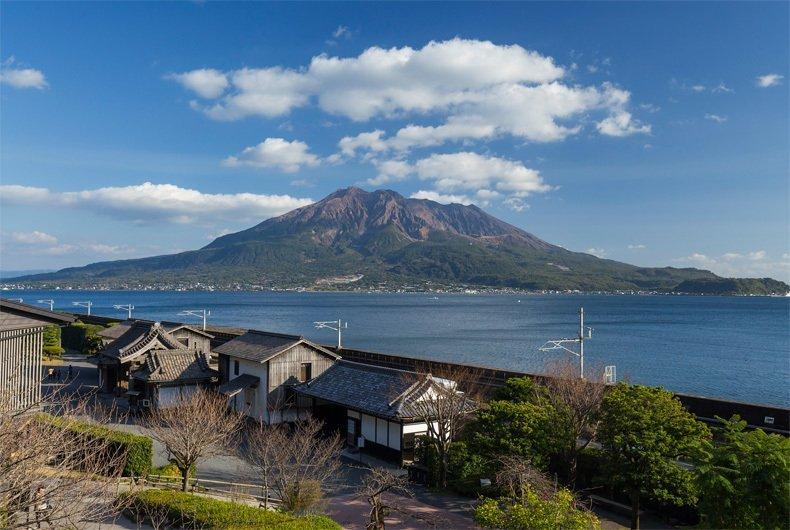

このブログの作者が最初に大学教員として赴任した鹿児島の桜島 (写真は鹿児島観光サイト かごしまの旅 ホームページより)

母校への赴任と呼吸ノイローゼ

三十代の最初のころ、鹿児島県のある短期大学助教授 (2007 年から准教授という名称に変更された) から、福岡県の母校の助教授になったとき、ストレスのためか心身の調子が悪くなった。恩師が母校へ呼んでくれたことが嬉しくて、張り切り過ぎたのかもしれない。

まもなくやけに呼吸が気になりだした。この呼吸が止まれば、すぐに死ぬことなので、それからいつも呼吸に注意をしていた。私は自分で「呼吸ノイローゼ」と称していたが、特に就寝前がつらかった。今は呼吸しているが、寝ている間に呼吸が止まり、死んでいるのではないかと考えると不安で仕方なかった。

この状態が数年間続いたであろうか。苦しい日々であった。本来であれば、仕事にエネルギーを傾注すべき三十代の働き盛りが、途方もない思いのために、毎日をうつうつと過ごすことになった。

あまりにも生に執着していたので、少しでも生から遠ざかる兆候があれば、見過ごしにできなかったのであろう。それから時が経った最近では、年を取ったせいか、死への恐怖が相当薄らいでいるので、「呼吸ノイローゼ」もそれほど気にならない。

「呼吸ノイローゼ」を完全に克服できたのは、渡辺利夫の『神経症の時代ーわが内なる森田正馬』 (TBSブリタニカ、1996年)を読んだからだ。どのような経緯からこの本を購入したのか、今となっては明らかでないが、森田療法には以前から興味があったので、森田正馬の文字に惹かれて、この本を購入したのかもしれない。

『神経症の時代ーわが内なる森田正馬』

渡辺利夫先生 (この方の著書から救われたので、私は先生と呼びたい) は、東京工業大学の教授を勤められ、定年後に拓殖大学の総長をされた経済学者である。 『神経症の時代ーわが内なる森田正馬』は 1996 年出版であるから、先生が東京工業大学の助教授の時の作品である。大学教員を勤めながら、このような著書を書かれた先生は、才能豊かな方である。

この著書の 90 ページで、私が陥っていた苦境をずばり言い当てられていた。渡辺先生は次のように書いておられる

脅迫神経症者は、苦悩の呪縛から逃れようと、抽象的知識を用いてさまざまな工夫を凝らし、しかし工夫を細心に凝らせば凝らすほど、いよいよ抜きさしならぬ苦悶にとらわれていく。このさまを、正馬は禅でいう「繋驢桔」(けろけつ) にたとえている。けつ (杭のこと) につながれた驢馬が、この杭から身を遠ざけようとしてあがき、杭のまわりをぐるぐる回転しているあいだに、ついに自分から杭に固く縛り付けられて身動きできなくなるようなものだという。自己の感情をなんらかの知識の体系から導きだした論理をもって克服しようと努力し、いっそう深い抑鬱に陥っていくことを戒めているのである。

92 ページには次のように書いておられ、私の進むべき道を示していただいた。

煩悶とか苦悩というものは、理知をもってしてはこれから解放されることはない。煩悶、苦悩、苦痛のそのあるがままになり切ることである。苦痛になり切ってしまえば、その苦痛はすでに苦痛でないと正馬はみていた。

その後の 93 ページから 94 ページまでは、私の肺腑を抉るような言葉であり、私の心中を見透かされたようであった。

「苦悩のあるがままになり切る」という心的態度の陶冶の重要性は、苦悩をやりくりすることなくそのままで耐え忍んでいれば、人の心は時間の経過とともに一点にとどまっていることはできず、どこか別のところに向かって流転していくはずだとみなす、正馬のもう一つの人間観に由来している。

「吾人の身体機能、精神現象は、時々刻々の絶えざる変化流動である。川の水が流れ流れて止まらないようなものである。吾人の欲望や苦痛恐怖も、決して三次元の空間のように、実体的なものとして固定的に考えてはいけない。ただ吾人はこれを想像し、思想することはできるけれども、実際の事実としては存在しない。すなわち欲望も苦痛も、時間の第四次元により絶えず変化、消長、出没するものであって、決してこれに拘泥することも、これを保留することもできない。快楽、苦痛も、ただ快楽を快楽とし、苦痛を苦痛としてそのままでよい。ことさらに快楽を大きくし、苦痛を軽くしようとしても、追ついた話ではない。それは不可能なことである。ただ、ときの経過にまかせるよりほかにない」変化流転する人の心をみつめて、正馬は「すべからく往生せよ」という。往生して時間の経過に身をゆだねれば、心はそのおきどころを次々と変えていって、苦悩は過ぎ去る。

呼吸が止まることはあり得ないのに、呼吸が止まると妄想して苦しむのは、まさに強迫神経症の何物でもない。あまりにも強い生への欲望のために、少しでも死に近づく道があれば、許せなかったのであろう。そのためか呼吸の停止というあり得ないことを想像して苦しんでいた。

ある女性の心臓恐怖症

ある女性が寝る前に心臓が止まるのではないかという恐怖に悩んでいた。その女性に森田は「心臓を止めてみなさい。どのように止まるか、今度私に報告してください」と言ったようである。その女性は次の診察で笑いながら「心臓を止めることはできませんでした」と森田に報告したそうだ。それから心臓神経症は彼女にまったく起きなかった。

私の呼吸神経症も同じで、呼吸が止まることを正面から受け止めることが肝要であった。そうすると人間の常で、呼吸のことを考えることはやめて、他のことを考えるようになる。人間の心理は一か所に留まることはない。いつも変転しているようである。呼吸恐怖症から逃れようと、様々な創意工夫をしている間は、呼吸の観念から離れることはできないが、呼吸の観念にこちらから飛び込んでいくと、呼吸への恐怖は消えていく。

最近、禅に凝って、時々座っているが、数息観ができない。数息観とは、呼吸に合わせて一から十まで数を数え、心を静かにする手法であるが、それが三か四で雑念が起き、数を忘れてしまう。若い時の呼吸恐怖症は、完全に消失している。

(English)

Appointment to My Alma Mater and “Respiratory Neurosis”

In my early thirties, when I moved from my position as an assistant professor at a junior college in Kagoshima Prefecture (the title was renamed to associate professor in 2007) to become an assistant professor at my alma mater in Fukuoka Prefecture, I began to feel physically and mentally unwell, perhaps due to stress. I was so delighted that one of my mentors had invited me back to my alma mater that I may have pushed myself too hard.

Before long, I became strangely preoccupied with my breathing. If my breathing were to stop, I would die instantly, and so I began constantly monitoring it. I jokingly referred to this as my “respiratory neurosis,” but it was especially painful at bedtime. I knew I was breathing now, but the thought that my breathing might stop while I was asleep—and that I might die—made me unbearably anxious.

This condition continued for several years. They were difficult days. My thirties should have been a time of peak productivity, when I could dedicate my energy to my work, but because of these overwhelming thoughts, I spent my days in gloom.

I was so fixated on life itself that I could not ignore even the slightest sign that seemed to pull me away from it. Perhaps because I am now older, and my fear of death has considerably diminished, my “respiratory neurosis” no longer troubles me as much.

What allowed me to overcome this “respiratory neurosis” completely was reading The Age of Neurosis: My Inner Morita Shoma by Toshio Watanabe (TBS Britannica, 1996). I no longer remember how I came to purchase this book, but since I had long been interested in Morita therapy, perhaps I was drawn to Morita Shoma’s name on the cover.

“The Age of Neurosis: My Inner Morita Shoma”

Professor Toshio Watanabe—whom I call “Professor” out of gratitude, as his book saved me—is an economist who served as a professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology and later became the president of Takushoku University after retirement. Since The Age of Neurosis: My Inner Morita Shoma was published in 1996, it must have been written while he was an associate professor at Tokyo Tech. For a university professor to produce such a book shows remarkable talent.

On page 90 of this book, Watanabe precisely identified the very predicament I had fallen into. He writes:

“The obsessive neurotic, in an effort to escape the shackles of suffering, devises various strategies based on abstract knowledge. Yet the more meticulously these strategies are crafted, the deeper the sufferer becomes entangled in inescapable agony. Shoma likens this to the Zen metaphor of keroketsu—a donkey tied to a stake (ketsu). The donkey struggles to move away from the stake, but as it circles around it, it ends up binding itself even more tightly to the stake, eventually unable to move at all.

He warns against attempting to overcome one's emotions through logic derived from some system of knowledge, for such efforts lead only to deeper depression.”

And on page 92, he offers the path I should take:

“Distress and suffering cannot be escaped through reason. One must become one with the very existence of that distress and suffering. Shoma believed that when one fully becomes the suffering itself, it no longer remains suffering.”

The words that follow, from pages 93 to 94, pierced me to the core, as though he had seen straight into my heart:

“The importance of cultivating the mental attitude of ‘becoming one with suffering as it is’ stems from Shoma’s view that if one simply endures without attempting to manipulate or manage suffering, the human mind—unable to remain fixed at a single point—will inevitably drift elsewhere as time passes.

‘Human bodily functions and mental phenomena are in constant flux, changing from moment to moment, like the flowing water of a river that never stops. Our desires, pains, and fears must not be regarded as fixed, solid entities in three-dimensional space. We may imagine or conceptualize them, but they do not exist as actual fixed facts. Desires and pains, governed by the fourth dimension—time—are constantly changing, appearing and disappearing. We cannot cling to them nor preserve them.

Pleasure is simply pleasure, pain simply pain; they are fine just as they are. To try to increase pleasure or reduce pain is futile—it cannot be done. One has no choice but to entrust it to the passage of time.’

Observing the mind’s ceaseless transformation, Shoma says, ‘One must surrender.’ When one surrenders and entrusts oneself to time, the mind will continually shift its focus, and suffering will pass.”

Although it is impossible for breathing to stop on its own, the fear that it might and the suffering that followed were nothing other than classic obsessive neurosis. My desire to cling to life was so strong that I could not tolerate even the slightest path that seemed to lead toward death. That is why I tormented myself with the impossible idea that my breathing might stop.

A Woman with Cardiac Phobia

There was a woman who suffered from the fear that her heart might stop while she slept. Morita reportedly told her, “Try stopping your heart. Tell me how it goes at your next visit.”

At her next appointment, the woman said with a laugh, “I couldn’t stop my heart,” and from then on she never again experienced cardiac neurosis.

My own respiratory neurosis was the same: it was essential to face the fear of my breathing stopping head-on. Then, as is human nature, once I confronted it directly, I gradually stopped thinking about my breathing and turned my mind to other things. The human mind never stays in one place; it is always shifting. While one is desperately trying various strategies to escape breathing-related fears, one cannot escape the obsession. But when one deliberately dives straight into the fear, the fear of breathing itself dissolves.

Recently, I have taken an interest in Zen and sit in meditation from time to time, but I am unable to practice susokukan, breath counting. This method involves counting breaths from one to ten to calm the mind, yet distracting thoughts arise at the count of three or four, and I lose track.

My youthful fear of breathing, however, has completely vanished.