常野ー江戸時代の女性 (Tsuneno--A Woman in the Edo period)

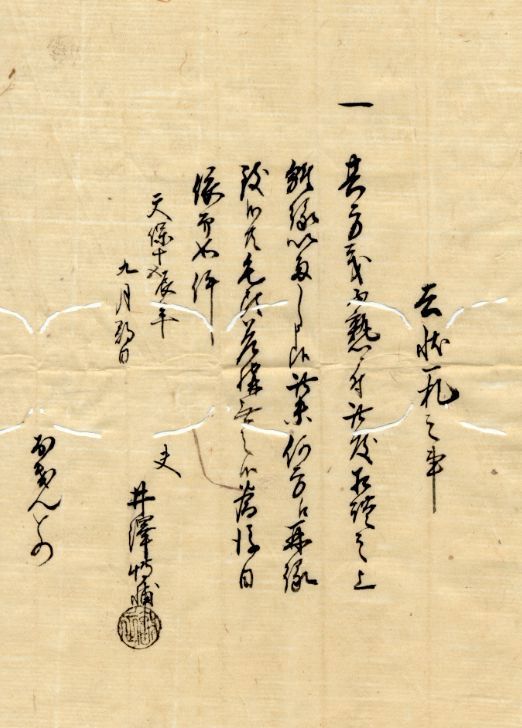

常野が渡された離縁状 新潟県立文書館蔵

文中は「おきんどの」とあるが、常野のことを指す

アメリカ人の歴史家である Amy Stanley から、江戸時代に実在した常野という女性について教えてもらった。Amy Stanley は「新潟県立文書館」で常野の資料を発見したとのことで、私もそのホームページを覗いてみた。

日本人女性 常野 の奔放な生涯

常野は当時としては珍しく4 度の離婚を経験している。若い時から江戸に憧れ、同郷の男に江戸に連れて行ってもらうが、貧窮の生活を送り、50 歳で亡くなったようだ。彼女の奔放な生涯が、アメリカ人歴史家の興味を引いたようである。

Amy Stanley はまず常野の出生と性格について説明する。

Tsuneno was an ordinary woman who was born into a Buddhist priest’s family in a tiny village in Japan’s snow country in 1804. She wasn’t uniquely talented or accomplished, but she did have a strong personality, and she was never content to live a conventional life in the countryside.

(訳) 常野は1804年に日本の雪国にある小さな村の仏教僧の家庭に生まれた。彼女は独自の才能も教養もなかったが、強い性格を持ち、田舎での因習的な生活には決して満足しなかった。

新潟県立文書館

常野という当時としては奔放な女性を知ったのは、「新潟県立文書館」であったと告白する。

I discovered Tsuneno’s story while I was searching online archives, looking for materials to translate and assign to my students. I ended up on the web page of the Niigata Prefectural Archives, looking at their “Internet Document Reading Course,” which was a series of posts meant to introduce the public to some of the interesting materials in their collection.

(訳) 私が常野の物語を発見したのは、私の学生に翻訳して宿題にする素材を探して、オンラインの古文書館を検索していた時であった。私はついに「新潟県古文書館」に出くわし、その「インターネット資料読解コース」を見た。それは収蔵品の中で興味ある素材を、一般の人に紹介する一連の記事であった。

次に Amy Stanley は、常野が江戸にどのようにして行ったかを、英文で説明する。

Tsuneno was in her mid thirties and had already been divorced three times when she decided to run away to Edo, the city she had always wanted to see. But as a woman, she couldn’t go alone; she needed an escort. A man of her acquaintance offered to take her there, saying that he had family in the city who would welcome her, and though she was slightly apprehensive, she agreed to go with him.

(訳) 彼女がいつも見たいと思っていた江戸に逃げようとしたのは、彼女が30 代半ばですでに3 回離婚していた。しかし女性であるため、一人では行けなかった。彼女には付き添いの男性が必要であった。知り合いの男性が、彼には常野を受け入れてくれる家族が江戸にあるからと言って、江戸に連れて行くと申し出た。彼女は少し心配であったが、彼と行くことにした。

アメリカ人が日本の歴史を研究する困難を次のように述べる。私も日本人でありながら、英文学を専門にしていたので、その苦労はよくわかる。

The challenges of my particular field—early modern Japan—are endless. The documents are difficult to read, because they’re mostly in an archaic form of Sino-Japanese where half the words are read backwards. All the manuscripts look like a chaotic squiggly mess.

(訳) 私の特殊な分野(近代初期の日本)にある難題は、数限りない。ほとんど日本と中国の古い形式で書かれており、言葉の半分は逆読みするので、資料は読みにくい。すべての写本は、混乱してごた混ぜのように見える。

歴史家には二種類の型がある

最後に彼女の歴史家に対する考え方が興味深いので引用しておく。彼女によれば、歴史家には二種類あるという。

I think there are basically two kinds of historians. Some want to explain how the world we live in came to be this way (and, by implication, how it might be changed). Others want to understand the past in order to cultivate an empathetic imagination—how can you make sense of people who were very different from you and everyone you know? I think both kinds of historian can be found in every field, geographically and temporally.

(訳) 私が思うに、基本的には、二つの種類の歴史家がいる。ある歴史家は、私たちが暮らす世界が、どのようにしてこんなになったかを説明したいと思う(そして暗にどのように変化していったかを)。他の歴史家は、感情移入する想像力を涵養するために過去を理解したいと思う。感情移入する想像力とは、あなたやあなたが知っているすべての人と異なる人々を、どのように理解するかということである。

外国人から日本の歴史を教えてもらうのは面白い。日本のことは私の方がよく知っていると思いながら、思いもしない角度から日本を解釈する態度には、いつも驚かせる。