シェイクスピア作品における女性 (Female Characters in the Works of Shakespeare)

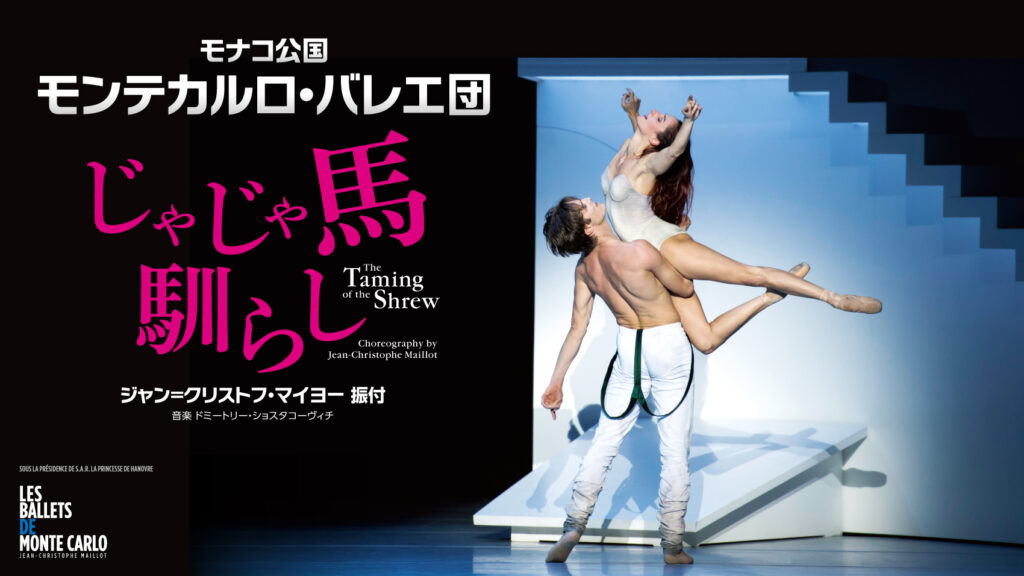

じゃじゃ馬馴らし モンテカルロ・バレエ団

このブログで、家父長制について論じましたが、今回はシェイクスピア作品における女性の立ち位置について考えてみたいと思います。

シェイクピアの時代では、家父長制が主流の考えですが、その風潮の中で女性がどのように描かれているか、興味ある問題です。

「家父長制」という言葉の意味を、広辞苑第七版 (岩波書店、2018) で引いてみますと、「家父・家長の支配権を絶対とする家族形態」と、抽象的な定義が書いてあります。あまりに抽象的ですので、同じ広辞苑で「家長権」という項目を調べてみると、「家族制度において、家長が家族に対して持つ支配権。古代、中世においては、家族の生命・財産はその下に支配された。ローマ法の家父権はその一典型。日本の旧制における戸主権もその一種」とあります。この定義のほうが、「家父長制」の定義より分かりやすいようです。

"patriarchy" と同じような系統に属する英語の言葉として "primogeniture" があり、日本語に訳しますと「長子相続制」で、 Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary 9th edition (Oxford University Press, 2015) では、"the system in which the oldest son in a family receives all the property when his father dies" と定義されています。父親が死亡したとき、家族のすべての所有物は、長男が受け継ぐシステムです。人間の社会では、男性が中心の社会をこれまでは築いてきたようで、女性の権利主張は、まだ歴史が浅いようです。

ところで、シェイクスピアの作品では、一見、男性が社会の中心と見えますが、仔細に作品を読み解いていくと、必ずしもそうではありません。女性の果たす役割はかなり大きいと言えます。『アントニーとクレオパトラ』 (Antony and Cleopatra, 1606-07) では、クレオパトラが権謀術数を使い、シーザーとアントニーを手玉に取っているし、『十二夜』 (Twelfth Night, 1601-02) では、女主人公であるバイオラの活躍が中心に描いてある。『マクベス』 (Macbeth, 1606) では、マクベス夫人が、夫マクベスをダンカン殺害へと導きます。

だが、『じゃじゃ馬馴らし』 (The Taming of the Shrew, 1593-94) などに代表される作品群は、女性が社会の厄介者、社会の負の存在として描写されていることが多い。『ヘンリー六世』 (Henry VI, 1689-91) 第一部に登場するジャンヌ・ダルクは、悪魔と結託した堕落した女預言師とされているし、『コリオレイナス』では、あまりにも息子に大きな影響を持った母親が、息子の社会的存在を抹消するケースも描かれている。

しかし、シェイクスピアが晩年に執筆した一連のロマンス劇と呼ばれる作品では、女性がかなり比重をおいて取り上げられています。『冬物語』 (The Winter's Tale, 1610-11) で、シチリア王のレオンティーズから不倫を疑われた王妃ハーマイオニーは、16 年間という苦しい年月を耐えて、最後には王家の再結集を促します。この作品では、男性の嫉妬が醜く描かれており、家父長制の男性中心世界では、世の中は上手く行かないことを例証しています。『シンベリン』 (Cymbeline, 1609-10) では、ブリテン王シンベリンの王女イモージェンが活躍して、女性の真価を発揮しています。

シェイクスピアの作品で注意すべきは、当時はエリザベス女王 (Elizabeth I, 1533-1603) という女性がイングランドを統治していたことです。彼女の存在は家父長制と真っ向から対立するものであり、エリザベス朝の作品は、その現実との葛藤に満ちていると言っても過言ではありません。

『ヘンリー五世』 (Henry V, 1387-1422) の注釈をしている著名なシェイクピア研究者 Andrew Gurr は、家父長制が脆いシステムであることを、次のように指摘しています。

By the 1540s one major lesson from the long dynastic conflict in England called the Wars of the Roses was evident: primogeniture, inheritance by the eldest son, was no secure guarantee of a clear title to the succession. Andrew Gurr (ed.), King Henry V (Cambridge University Press, 1992), p.18.

(訳) 1540 年代までのバラ戦争と呼ばれた長い王家の争いから得られた大きな教訓は、明らかであった。それは、長男の相続による長子相続性は、王家相続者の明確な資格を保証するものではなかった、というものである。

ランカスター家とヨーク家の 30 年間におよぶ王位継承権争いは、家父長制や長子相続システムが、安全で無欠なものではないことを示しています。

シェイクスピアの作品を詳細に眺めてみれば、女性の描写の中に、家父長制の綻びが垣間見えるようで、興味を惹かれます。

(English)

In this blog, I have discussed "patriarchy", and this time I would like to consider the position of female characters in Shakespeare’s works.

In Shakespeare’s time, patriarchal values were dominant, and it is an intriguing question how women were depicted within that prevailing outlook.

Looking up the meaning of the term kafuchōsei (“patriarchy”) in the 7th edition of "Kōjien" (Iwanami Publishers, 2018), we find an abstract definition: “a family structure in which the authority of the patriarch or family head is regarded as absolute.” Because this definition is rather abstract, I looked up the entry kachōken (“patria potestas”) in the same dictionary, which states: “In the family system, the right of control that the family head possesses over the family. In ancient and medieval times, the lives and property of family members were under his authority. The patria potestas under Roman law is one such example. The authority of the household head in Japan’s former legal system is also a variation of this.” This definition appears easier to grasp than that of “patriarchy.”

An English word belonging to the same conceptual family as patriarchy is primogeniture, translated into Japanese as chōshi sōzokusei (the system of inheritance by the eldest son). The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, 9th edition (Oxford University Press, 2015), defines it as “the system in which the oldest son in a family receives all the property when his father dies.” Under this system, upon the father’s death, all family property is inherited by the eldest son. Human societies seem largely to have been built around male-centered structures, and women’s assertion of rights is still relatively new in historical terms.

At first glance, men appear to dominate the social sphere in Shakespeare’s plays, but a close reading reveals that this is not necessarily the case. Women often play significantly important roles. In Antony and Cleopatra (1606–07), Cleopatra employs various political intrigues and manipulations to outmaneuver both Caesar and Antony. In Twelfth Night (1601–02), the narrative centers on the resourcefulness and vitality of the female protagonist, Viola. In Macbeth (1606), Lady Macbeth leads her husband toward the murder of King Duncan.

However, in works such as The Taming of the Shrew (1593–94), women are frequently depicted as nuisances to society or as negative forces. Joan of Arc, who appears in Part 1 of Henry VI (written 1589–91), is portrayed as a corrupt prophetess in league with the devil. In Coriolanus, a mother who wields excessive influence over her son ultimately contributes to the destruction of his social standing.

Yet in the group of plays commonly called the “late romances,” which Shakespeare wrote toward the end of his career, women are depicted with considerable emphasis. In The Winter’s Tale (1610–11), Queen Hermione, who has been falsely accused of infidelity by Leontes, King of Sicilia, endures sixteen long years of hardship and eventually helps bring about the restoration of the royal family. The play vividly portrays the ugliness of male jealousy and illustrates that a male-centered patriarchal world cannot function smoothly. In Cymbeline (1609–10), Imogen, daughter of King Cymbeline of Britain, demonstrates her true worth through her actions.

It is also important to remember that during Shakespeare’s lifetime England was ruled by Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603), a woman. Her presence stood in direct opposition to the principles of patriarchy, and it is no exaggeration to say that Elizabethan literature is rife with tensions created by this historical reality.

Andrew Gurr, a distinguished Shakespeare scholar who annotated Henry V, points out the fragility of the patriarchal system as follows:

By the 1540s one major lesson from the long dynastic conflict in England called the Wars of the Roses was evident: primogeniture, inheritance by the eldest son, was no secure guarantee of a clear title to the succession.

—Andrew Gurr (ed.), King Henry V (Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 18.

The thirty-year struggle over succession between the Houses of Lancaster and York demonstrates that patriarchy and the system of primogeniture are far from safe or flawless.

A close examination of Shakespeare’s works suggests that within his portrayal of women, we can catch glimpses of fissures in the patriarchal system—an aspect that proves quite fascinating.